Tamil Survival Stories: Indra

- 13th October 2016

- POST IN :SOCIETY

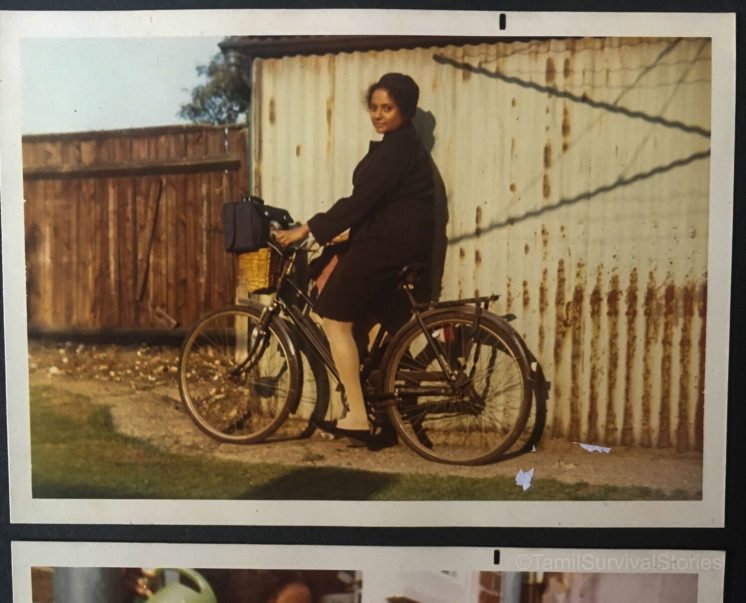

INDRA

London, United Kingdom

1965

Our ship was like a floating luxury village. I shared a berth with the three other single Tamil women on the boat, who like me, were heading to the UK to study nursing.

Before we awoke, a newsletter would be pushed under our door, which detailed the news and events of the day. With a tap on the door a crew member would serve us biscuits and orange juice – we would still be in our nighties. Sometime in the morning our sheets would be changed. It was like nothing we had experienced before.

Between 8 and 10am we would be served an English breakfast in a large and very posh dining hall. We had a choice of fruits, cereals, bacon and eggs, juices and breads. We tried most things with curiosity and timidity.

I mostly remember missing home and being heartbroken that I was enjoying such such comforts without my parents and siblings. Even eating an apple was painful.

After breakfast we had numerous choices to pass our time. We could wash our clothes at the laundry, we could go to the medical clinic if we had ailments, we could play games or attend creative workshops. There was a swimming pool and a number of shops. We enjoyed sitting on the deck and watching the sunsets. Everyone admired our sarees and we enjoyed showing them off.

We spent our time writing letters to our family back in Ceylon. We would post them at the post office on the boat.

In the afternoons we would watch movies in a little theatre that seated about 100 people. This is where I watched Goldfinger and Dr Who.

We were able to get off of at the ports, sometimes for a day, sometimes for a few hours. I remember stopping at Bombay, Aden and Barcelona. We stuck to our little group and curiously soaked in all the new sights, smells and sounds.

The journey took 18 days and went through the Suez Canal. The P&O liner had picked us up in Colombo along with three or four other Tamil families. They had likely paid full price for their passage and were wealthy.

Appa had paid a small fee for my passage. I can’t remember how much it cost. Our group of four women were the second intake of Tamils from Sri Lanka to arrive here as part of the UK’s international recruitment drive for nurses.

A few years before my departure to the UK, I had answered an ad to be an air hostess for Air Ceylon. They were only recruiting for two positions. My application was successful and on the eve of the morning I was to attend my trial flight, my teacher, not wanting me to disrupt my studies, intervened and made appa stop me from accepting this posting. I was devastated.

The next opportunity that knocked at my door was being selected as one of the two people out of the whole island for dental nursing training at a university in Ceylon. I was fluent in Sinhalese, English and Tamil, which I think worked in my favour.

When the Brits were in town recruiting nurses to be trained and for work in the United Kingdom, appa suggested I should apply. The selection process involved an interview in English and again, I was selected.

The ‘58 pogrom had disrupted the lives of all the Tamils on the island. Our family had to leave Colombo and move to Jaffna, which had an impact on our education and our everyday life. So we sought opportunities overseas. I had always intended to return to Ceylon after I finished my training.

I was 23 years old when I arrived in the United Kingdom on March 25, 1965. The warden of the West Herts Hospital at Hemel Hempstead came in a car to pick up our group of four Tamil women from the port at Waterloo. I can’t remember where the big boat had docked.

We were under the hospital’s care for three years. We stayed in the nurses’ quarters next door and attended classes at the hospital. Our study included work experience at the hospital. We were paid a salary, which we sent back home to our families.

The first nine months were terribly difficult. Our first winter was a shock. We definitely were not prepared for it. I bought my first winter coat and boots in that year.

Every three months a new group of nurses would arrive. Tamils arrived from Malaysia and Ceylon. Other groups arrived from Nigeria, Kenya and China.

In the evenings, the English girls were out with their boyfriends at pubs and clubs. Because of the culture differences, we didn’t join them. We would stay at home and study or chat to each other. It took us a while to understand all the accents – especially the Lincolnshire one – and it took them a while to understand us.

In those early years I missed Tamil food so much. When Tamils we knew came from the island, amma would send whatever she could – but what could she send? மோர் மிளகாய் (mor millagai – dried chilies marinated in yoghurt) and sometimes fried prawns and curry powder. There were no south Asian restaurants or spice shops. There was a YMCA at Lancaster Gate that served rice, dhal and sothi, but we couldn’t go there everyday.

Back then even though we experienced racism on the trains and in the workplace, I didn’t feel unsafe. We would go to central London to watch a late night movie, and didn’t hesitate to travel back to our homes at one or two in the morning. The most we would hear about is a couple of train robberies each year.

On the weekends we loved wearing our sarees and going into town. The people in little Hemel Hempstead had never seen women in sarees before. Cars would stop to admire us as we walked down the street and people would ask us if we were born with such a dainty walk. They were anxious to know how we wrapped six yards of clothes around ourselves. We foolishly did not wear cardigans when it was cold, because our sarees were so much admired, and maybe this is why we have now ended up with arthritis (laughing).

In those first months I thought of home all the time and cried every day. I wanted to run back there. My mother would reply to my letters saying that I had left for a reason and to achieve it before returning and to not give up this opportunity for an education. It was my mother’s encouragement that kept me strong. After nine months, I accepted my life and started to feel settled. I started enjoying my freedom and the company of new friends. When the violence in Ceylon escalated and the pogroms became frequent, my main priority was to get my six siblings and my parents out of there. Over time I was able to do this. I never thought about returning there to live. As Tamils we could no longer see a future there.

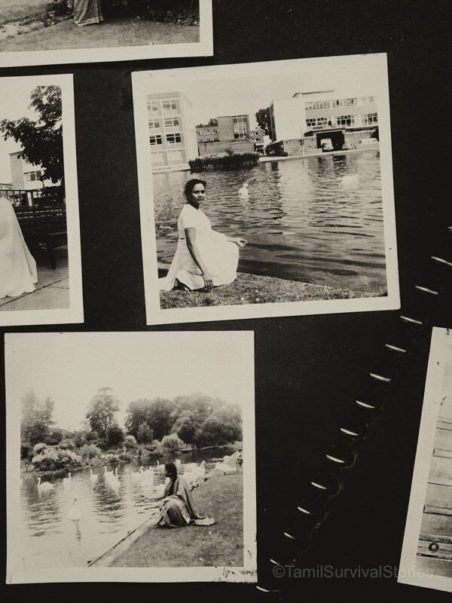

Tamil Survival Stories is a photographic journey into the survival of the Eelam Tamils, the preservation of their identity across the globe, and the role of women in this story. To find out more about the project please visit the Tamil survival Stories facebook page.

First image – Taken in 1969 at the medical ward of St Paul’s Hospital Hemel Hempstead for a local newspaper.